Language Support as a Scaffold AND a Stretcher

Every student we serve is growing in language. When we plan for instruction that is linguistically supportive, we want to remind ourselves that language supports should center on both scaffolding upward and also stretching outward. When we plan for language supports that do both, we are better serving and supporting every student’s language needs.

Every single human being we come into contact with has their own unique language journey - even if it’s a monolingual language journey! All of us have had experiences that have shaped and influenced how we language through reading, writing, listening, and speaking.

As we serve and support students with their own unique language journeys and lived experiences that have shaped how they engage with language, it’s important to recognize that

these journeys and experiences also impact how we see ourselves and others as languagers. I never got into the field of EL/ESL/Multilingual Learners because I’m passionate about verbs, nouns, or vocabulary. One big piece of my passion in this work is that I want students to feel equipped to be powerful communicators as they navigate and exist between and across different spaces and places. I want them to feel confident and empowered as languagers!

Because every adult teaches their content through language, all of us are, by default, language teachers. Since all of our students are growing in their languaging skills, all of them are language learners. Some of our students are monolingual language learners, and some are bilingual/multilingual language learners. This means that bringing language to the forefront will serve all students!

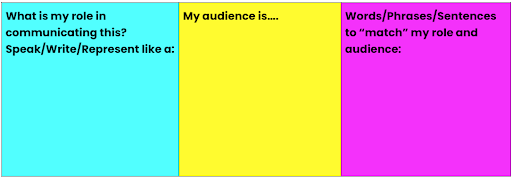

One way to support students in stretching their language skills is to have students identify a role and an audience for their languaging tasks. For example, when students have to dialogue with each other, they can identify a role. For example, when doing partner work, they might consider: am I speaking to another 5th grade student right now, or am I speaking to a cosmetics company regarding the safety of their ingredients for young consumers? This will help to inform their language choices.

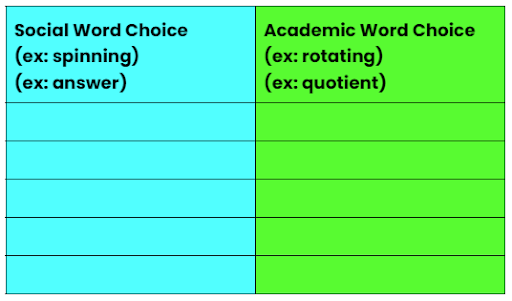

Another way to stretch students’ language skills is to make connections between “social” and “academic” vocabulary. Sometimes, folks want us to believe that “academic language” is somehow more valuable than social language. This is simply not true! Our students (and all of us) need BOTH social AND academic language to thrive in various contexts. We can liberate ourselves and our students from this belief that one set of languaging skills is superior. When we are teaching content-specific vocabulary or even technical vocabulary, have students make connections to other word choices that they might use. For example, I may use the word “rotation” when describing the path of planets around the sun, but I can easily link it to the word “spin” because that word is very familiar to me when I language with my peers. Creating space for those links is powerful!

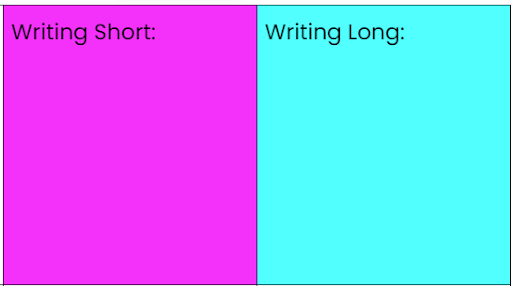

One final way to stretch language is to have students practice expression concisely AND in an extended manner. Students must be able to communicate in shorter genres (think of Tweets, social media posts, a headline, a thesis statement, a vision statement, etc.). Give students an opportunity to create a message in a “short” way and in a “long way.” It’s really powerful when students can see this side-by-side, like in a table that looks like the one below.

For a full set of templates like these, you can use this link for English and this link for Spanish. Recognizing that language support is not just about scaffolding upwards, it’s also about stretching outwards, will help us as educators to bring language to the forefront of what we do - and will help us to better serve all students!

Carly is a Thought Leader at

IDEAcon 2024. Make sure to add her sessions to your IDEAcon schedule as you build it in the attendee hub.

Carly Spina has 17 years of experience in Multilingual Education, including her service as an EL teacher, a third-grade bilingual classroom teacher, and a district-wide Multilingual Instructional Coach. She is currently a multilingual education specialist at the Illinois Resource Center, providing professional learning opportunities and technical assistance support to educators and leaders across the state. Her first book, Moving Beyond for Multilingual Learners, was published in 2021 by EduMatch Publishing.